Netaji Subash Chandra Bose, despite having distinct ideology and approach, had held Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad in such a high esteem that he had named three regiments or brigades of the first division of the Indian National Army after them.

Another INA guerrilla regiment was formed drawing on some of the finest soldiers of the three brigades and it was called Subhas Brigade despite being forbidden by Netaji to do so. Gandhi-Nehru-Azad were strong votaries of nonviolent resistance and moral persuasion, while Subash Bose believed in armed struggle and revolutionary action. This divergence in their strategies and philosophies was a significant point of difference between them but INA chief thought it fit to name his brigades after them

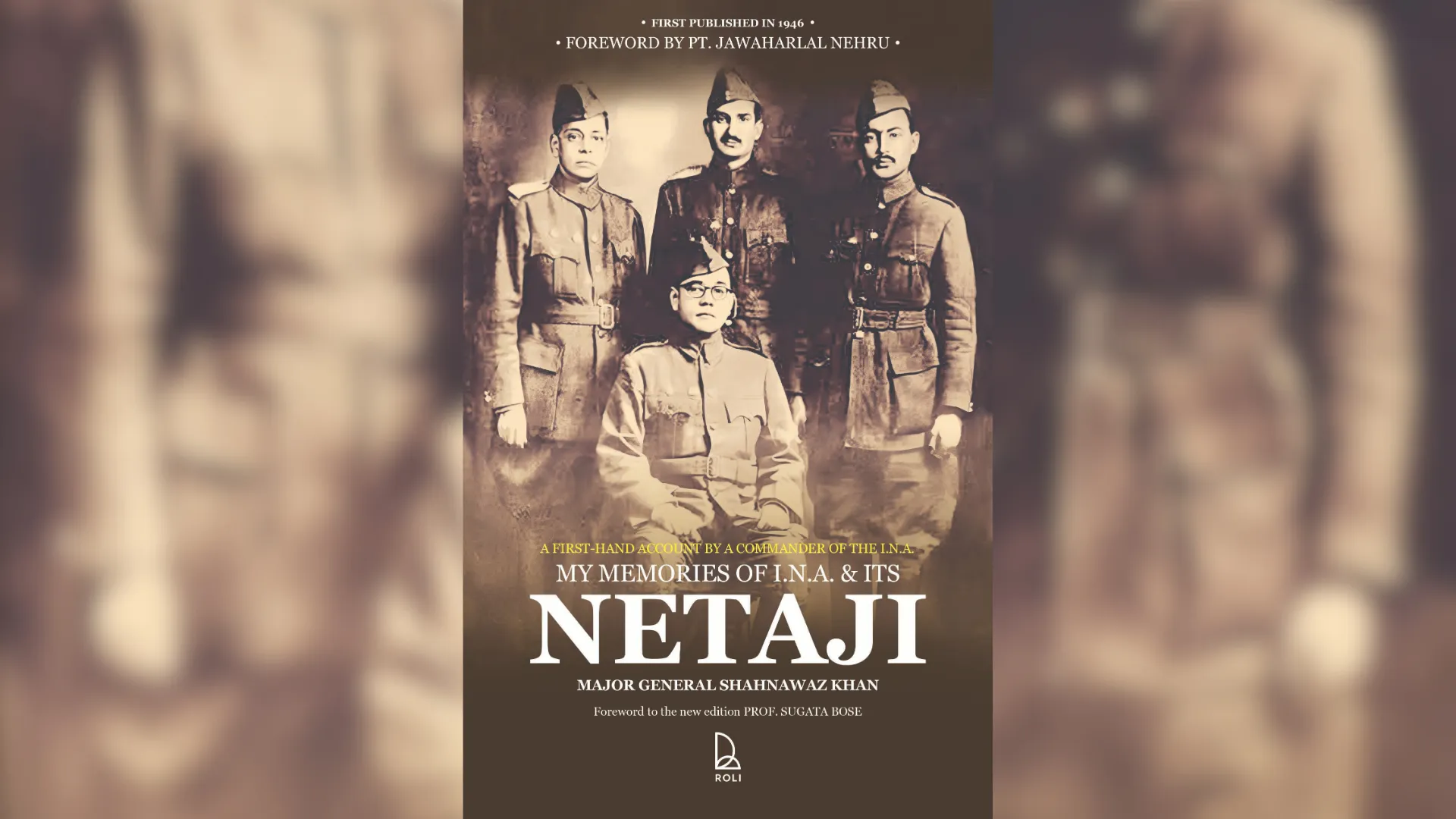

In “My Memories of INA and its Netaji [Roli Books 2025], the new edition of Major General Shahnawaz Khan’s account of Subash Bose and INA gives a vivid account of these brigades in the battles that were fought in Taiping, Malaya, from September 1943 onwards and its advance to Burma (present-day Myanmar) in late November 1943. The original work of Major General Shahnawaz Khan who served as a MP and minister in the Indira Gandhi cabinet, was first published in 1946.

A foreword by Professor Sugata Bose Gardiner Professor of History, Harvard University, USA in the new edition is packed with loads of information and anecdotes. Prof Bose quotes General Shahnawaz Khan how he was hypnotized by Subash Bose’s personality and his speeches. In 1943 when Shahnawaz had met Bose, the INA leader had placed a map of India. “… and for the first time in my life I saw India through the eyes of an Indian.” General Shahnawaz recalls that transformative moment as all along, he had been interested only in soldiering and sport. Many in Khan’s clan of Janjua Rajputs from Rawalpindi in Punjab had served in the British Indian Army. “Netaji challenged him to choose whether to owe allegiance to ‘the King or the country’. ‘I decided to be loyal to my country,’ Shahnawaz testified at his court-martial [ in famous 1945 INA trial held at the Red Fort, Delhi] and I gave my word of honour to my Netaji that I would sacrifice myself for her sake” reproduces Sugata Bose whose own work , “His Majesty’s Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle against Empire (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011, 2022) is considered as an authentic account of Subash Bose.

For taking the anti Raj instance, Shahnawaz was put on trial along with Prem Kumar Sahgal and Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon on the charge of waging war against the King-Emperor. During the trial in November and December 1945, the story of the saga of Netaji and his Indian National Army, recalled Prof Bose, had reached every corner of India. “The Indian people expressed themselves forcefully on the side of Netaji’s soldiers. The slogan ‘Lal Qile se aayee awaz, Sahgal, Dhillon, Shahnawaz’ reverberated across the length and breadth of the country. On 31 December 1945 at the Red Fort, the three were found guilty and sentenced to deportation for life, the same punishment that had been handed to Bahadur Shah Zafar in 1858.”

However, as Prof Bose documents in his foreword, within three days, on 3 January 1946, the then British Commander-in-Chief Claude Auchinleck was forced to release Sahgal, Dhillon, and Shahnawaz to a heroes’ welcome from the Indian public. Netaji and his I.N.A. had successfully undermined the loyalty of Indian soldiers to their British colonial masters and replaced it with a new devotion to the cause of free India even when the Union Jack was flying high at all seats of power in India.

In “My Memories of I.N.A. and its Netaji” Shahnawaz Khan says he noticed ‘a strange influence’ that his leader exercised over everyone who had met Subash Bose. “His was a personality which captivated everyone who met him, even foreigners. It was he and he alone who welded all Indians in East Asia into one unit and created a feeling of friendship and harmony among the nations of the East and its people. He was greatly loved and esteemed not as a sacred deity but as a man, as a hero, as a friend, and as a comrade.’

In addition to military facts, Prof Bose observes in his foreword how Shahnawaz supplied fine insights into the forging of national unity by Netaji and his INA. Interestingly, the most ardent supporters and admirers of Netaji were found among Muslims. As a leader, Netaji respected every man for what he was worth’ and not based on his religious or provincial identity. The Nagas, as Shahnawaz Khan records, ‘were most helpful to our troops.’ They bitterly recalled the humiliation heaped by the British on their queen. ‘All that we would like to have,’ they assured Shahnawaz, ‘is our own Raja, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.’ Describing a battle of the Gandhi Brigade against the Seaforth Highlanders on the outskirts of Imphal, Prof Bose quotes Shahnawaz as saying that that most of the INA troops taking part in that action were ‘raw Tamil recruits from Malaya’ who ‘acquitted themselves most creditably and smashed the British theory of martialand non-martial classes.’

After the INA’s march towards Delhi was halted in Imphal and Kohima, Sh a h n awa z r e c o u nt s the remarkable fortitude shown by INA soldiers and their leader during battles in Burma until the spring of 1945. Perhaps most moving is his telling of the breakout from being trapped in Meiktila towards Pyinmina on 26 February 1945:

Everyone looked cheerful. One thing was certain; the enemy would never capture us alive. When we entered the car and started off, Netaji was sitting with a loaded Tommy gun in his lap. Raju had two hand grenades ready. The Japanese officer was holding on to another Tommy gun and I had a loaded Bren gun in my hand. We were all ready to open fire instantaneously.

On reaching Pyinmina, Netaji expressed his desire to ‘fight his last battle against the British there’. Shahnawaz was eventually captured by the British near Pegu on 18 May 1945, after Netaji had made his epic retreat from Burma to Thailand on foot with some of his officers, soldiers, and women of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment. The Red Fort trial would turn their military defeat into a spectacular political victory.

Prof Bose writes how he had the privilege of meeting Shahnawaz Khan in the 1960s and early ’70s during his visits to Netaji Bhawan in Kolkata. At that time, General Shahnawaz Khan was working with Prof Bose’s father Dr. Sisir Kumar Bose to ensure the welfare of surviving veterans of the Indian National Army and grant them due recognition for their sterling contribution to India’s freedom. Shahnawaz Khan used to tell Prof Bose poignantly: ‘In those streams of blood of the soldiers of the Indian National Army, the blood of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians intermingled and flowed freely for one cause – a great, free and united India.’